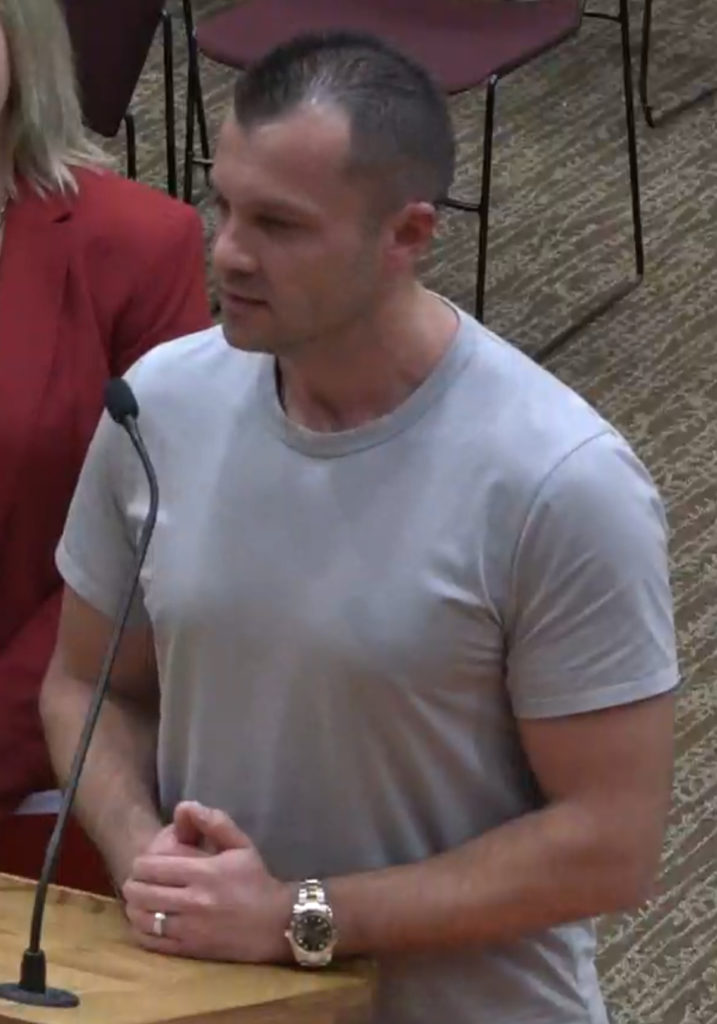

Should the city be mitigating risk when it comes to public art?

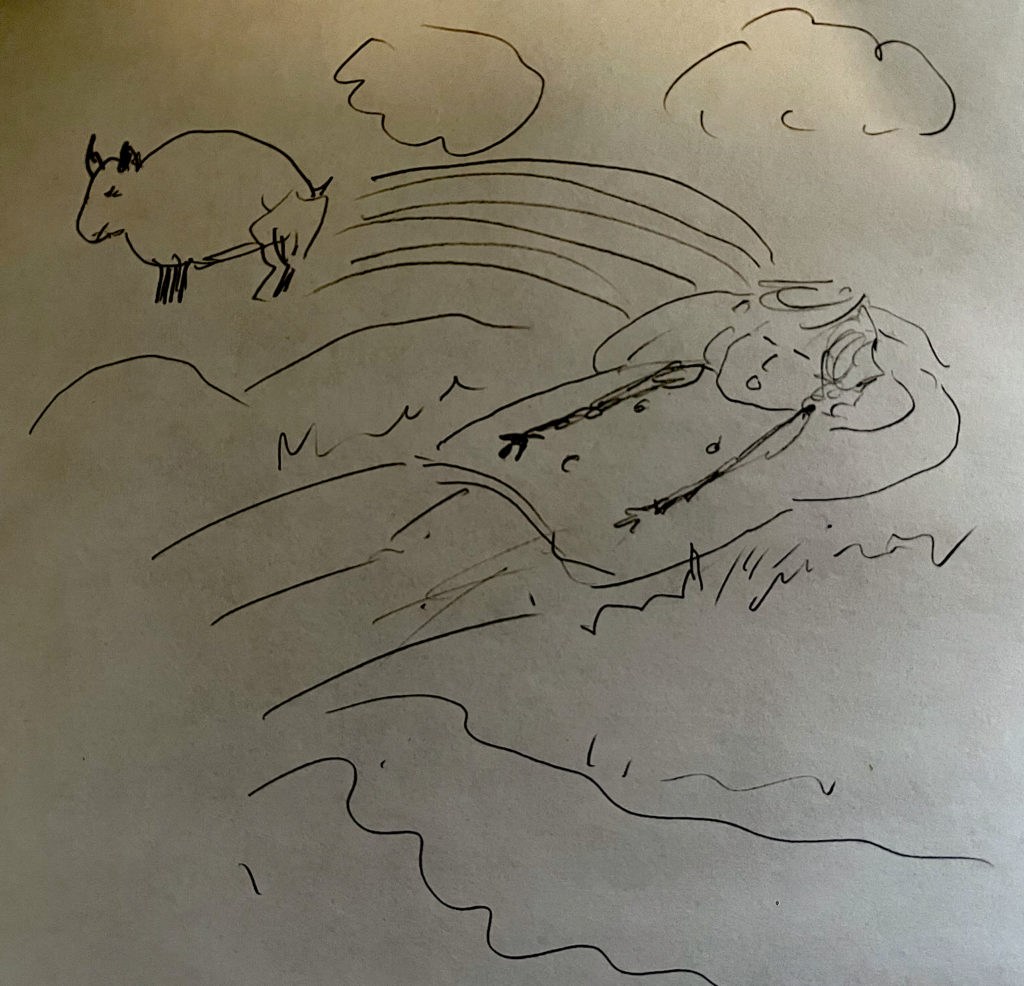

This is a rendering I did of what I was told the Bunker Ramp mural would have looked like. A Native American taking a nap next to a river dreaming of buffalos frolicking in a rainbow sky. I still have NOT seen the image.

Mr. Lalley is suggesting that is what the mayor exactly did when rejecting the selected mural choice and cancelling the project all together, mitigating risk;

This wasn’t a commissioned piece, as Boice had to explain to me, which could include parameters on the theme or content.

In this case, the intent was to allow the chosen artist “control the narrative,” as Boice put it.

That’s new.

It’s a great idea when you’re fostering and supporting artistic endeavors in your community.

For a government, for people who want other people to approve of what they do, it’s risky.

But you have to know that going in.

Rejection from the wider public is always a possibility. In my experience uncertainty is the artist’s constant companion, whether they are painters, musicians, sculptors, writers or quilters.

There’s always risk in art.

City government is inherently about mitigating risk.

We may never know the content of what was intended as a short-term mural, that was recommended by the Visual Arts Commission and rejected by the mayor.

Which highlights a more perplexing theme.

We may never know if the mural in question was patently offensive to one or more groups of people in the community.

We may never know if the mayor was reacting to some real or perceived public consequence if he approved it.

With public art comes public scrutiny.

Artists usually want that.

Government usually does not.

While I still struggle with this supposed offensive mural, you can only look a block away to a naked dude that has been standing there for 50 years (with a short stint in a parks and rec boneyard).

While it appears that the mayor was mitigating risk, it also suggests to me he was more worried about what Taupeville would think of the mural and not everyday folks.

Just another shirtless Native American in front of the Bunker Ramp of Democracy.

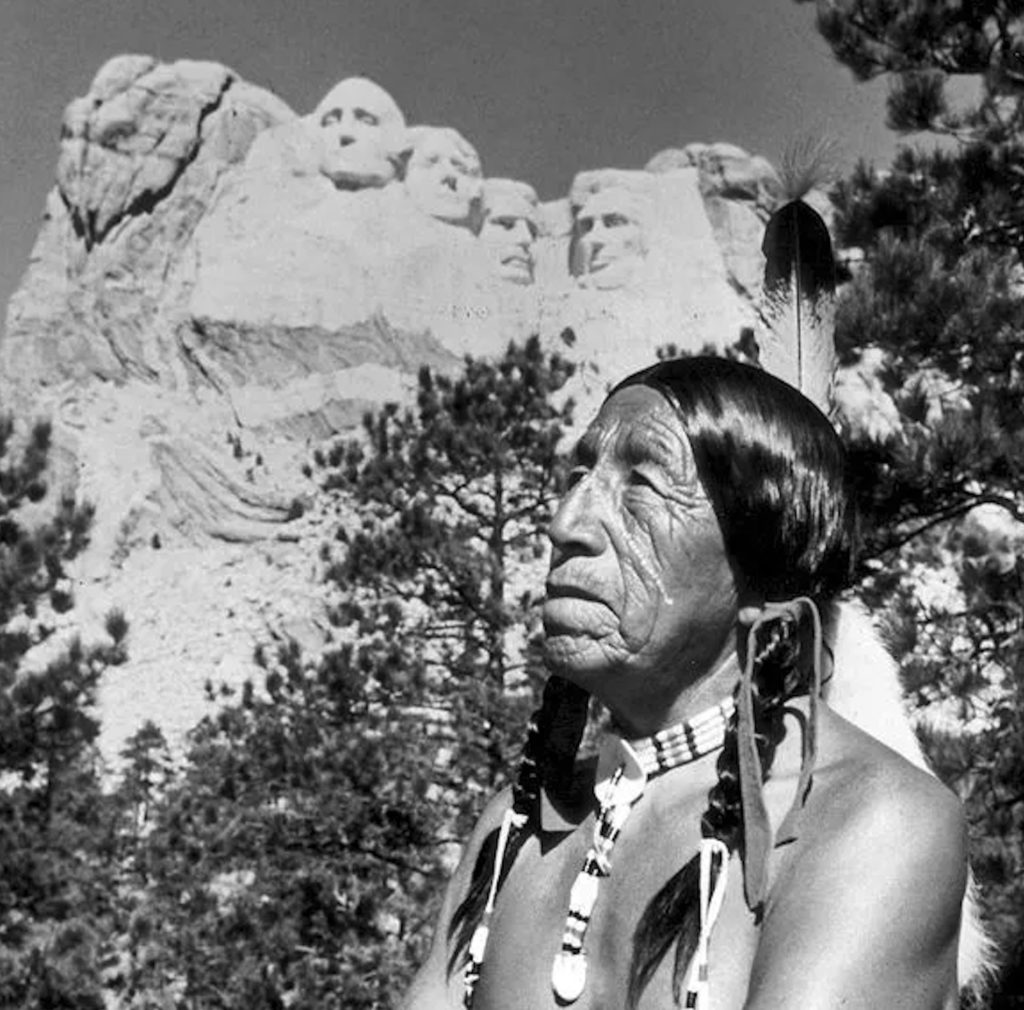

Which brings us to Ben Black Elk;

As the unofficial greeter at Mount Rushmore, Black Elk spent 27 years welcoming guests and promoting Native American culture. A Huron Daily Plainsman article noted that he posed for an estimated 5,000 photos daily during peak tourist season, earning Black Elk the distinction of being the most photographed Native American in the world. In addition to his photo record, the Sioux City Journal reported that Black Elk was the first person to have a live image broadcast over the Atlantic — via the Telstar satellite that launched in 1962.

It seems the state did a fine job of mitigating the risk of having a shirtless Native American pose for pictures in front of Mt. Rushmore now if we could just figure it out in Sioux Falls.