SCOTUS rules that elected officials cannot designate their FB pages as personal

Seems Mayor TenHaken may have to change his FB page;

The US Supreme Court ruled on Friday public officials with ability to make policy cannot claim a Facebook page is private. Public officials can be sued for blocking or deleting critical commentary, the opinion said, if a public employee has the “actual authority to speak on the state’s behalf” and “purported to exercise that authority” in the social media post at issue. A personal page status cannot be claimed if the public official is not personally moderating the content.

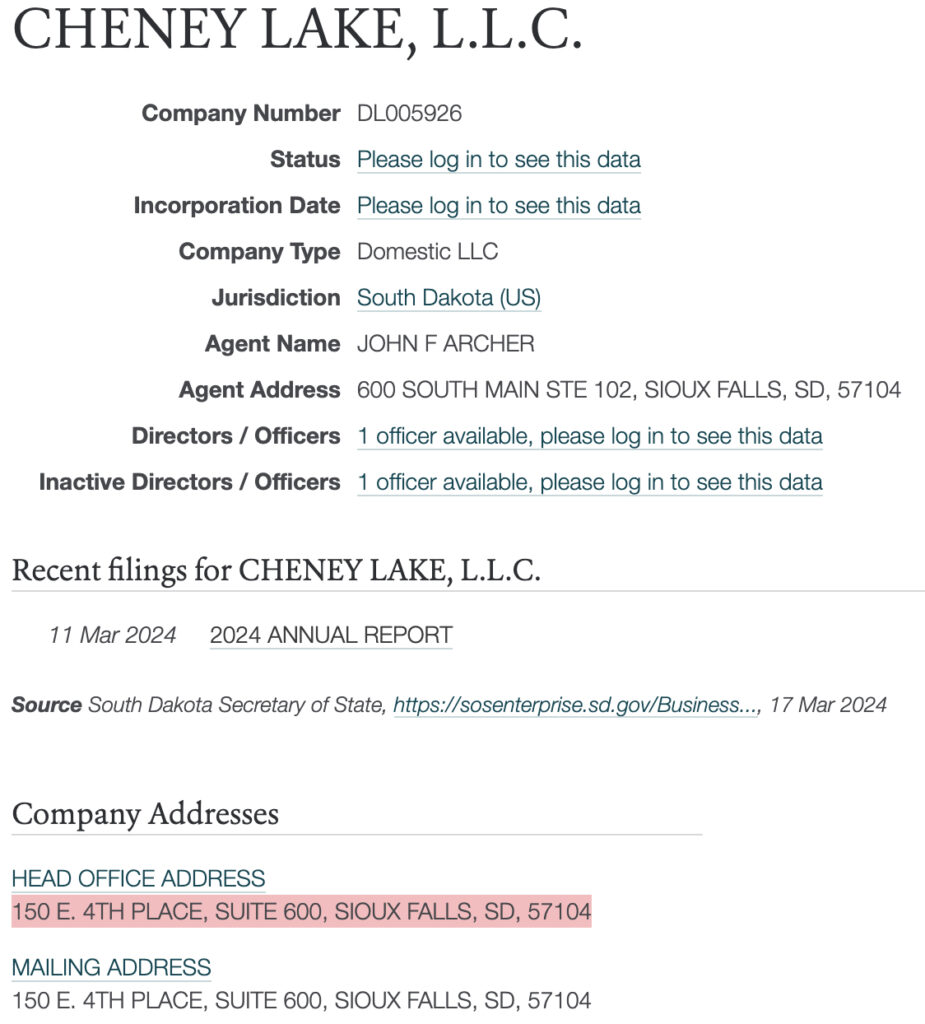

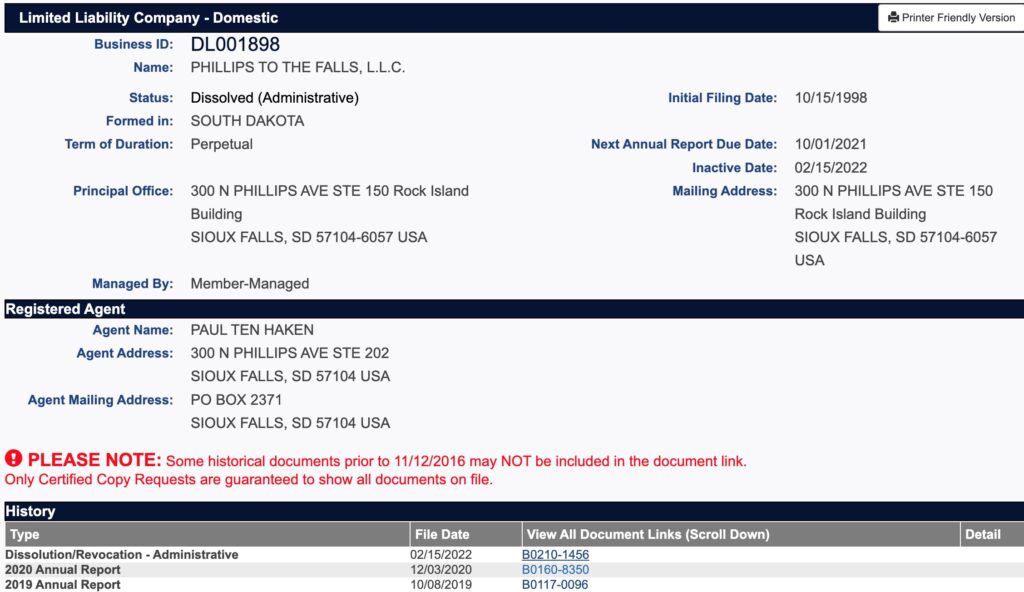

And Paul is paying someone to monitor the page. You know, the guy who moderated the council candidate forum. Basically the RULING says that as an elected official, you cannot have a personal page, and cannot censor commentary or users. Facebook is a public forum and when posting on there as an elected official, that would make it official.

James Freed, like countless other Americans, created a private Facebook profile sometime before 2008. He eventually converted his profile to a public “page,” meaning that anyone could see and comment on his posts. In 2014, Freed updated his Facebook page to reflect that he was appointed city manager of Port Huron, Michigan, describing himself as “Daddy to Lucy, Husband to Jessie and City Manager, Chief Administrative Officer for the citizens of Port Huron, MI.” Freed continued to operate his Facebook page himself and continued to post prolifically (and primarily) about his personal life. Freed also posted information related to his job, such as highlighting communications from other city officials and soliciting feedback from the public on issues of concern. Freed often responded to comments on his posts, including those left by city residents with inquiries about community matters. He occasionally deleted comments that he considered “derogatory” or “stupid.”

After the COVID–19 pandemic began, Freed posted about it. Some posts were personal, and some contained information related to his job. Facebook user Kevin Lindke commented on some of Freed’s posts, unequivocally expressing his displeasure with the city’s approach to the pandemic. Initially, Freed deleted Lindke’s comments; ultimately, he blocked him from commenting at all. Lindke sued Freed under 42 U. S. C. §1983, alleging that Freed had violated his First Amendment rights. As Lindke saw it, he had the right to comment on Freed’s Facebook page because it was a public forum. The District Court determined that because Freed managed his Facebook page in his private capacity, and because only state action can give rise to liability under §1983, Lindke’s claim failed. The Sixth Circuit affirmed.

Held: A public official who prevents someone from commenting on the official’s social-media page engages in state action under §1983 only if he official both (1) possessed actual authority to speak on the State’s behalf on a particular matter, and (2) purported to exercise that authority when speaking in the relevant social-media posts. Pp. 5–15.

One last point: The nature of the technology matters to the state-action analysis. Freed performed two actions to which Lindke objected: He deleted Lindke’s comments and blocked him from commenting again. So far as deletion goes, the only relevant posts are those from which Lindke’s comments were removed. Blocking, however, is a different story. Because blocking operated on a page-wide basis, a Court would have to consider whether Freed had engaged in state action with respect to any post on which Lindke wished to comment. The bluntness of Facebook’s blocking tool highlights the cost of a “mixed use” social-media account: If page-wide blocking is the only option, a public official might be unable to prevent someone from commenting on his personal posts without risking liability for also preventing comments on his official posts.3 A public official who fails to keep personal posts in a clearly designated personal account therefore exposes himself to greater potential liability.

* * *

The state-action doctrine requires Lindke to show that Freed (1) had actual authority to speak on behalf of the State on a particular matter, and (2) purported to exercise that authority in the relevant posts. To the extent that this test differs from the one applied by the Sixth Circuit, we vacate its judgment and remand the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

——————

3 On some platforms, a blocked user might be unable even to see the blocker’s posts. See, e.g., Garnier v. O’Connor-Ratcliff, 41 F. 4th, 1158, 1164 (CA9 2022) (noting that “on Twitter, once a user has been ‘blocked,’ the individual can neither interact with nor view the blocker’s Twitter feed”); Knight First Amdt. Inst. at Columbia Univ. v. Trump, 928 F. 3d 226, 231 (CA2 2019) (noting that a blocked user is unable to see, reply to, retweet, or like the blocker’s tweets).